If socialism is so great and capitalism is so terrible, should we dismantle capitalism and implement socialism?

No.

We cannot. A social system such as capitalism is not like a building that can be torn down, cleaned up, and something new built in its place. It's not even like the ship we must rebuild a piece at a time as we are sailing. Capitalism isn't something that we live under, it is what we are. You, her, I, we are capitalism. We have jobs, bank accounts, homes we rent or pay a mortgage for, superiors, subordinates: capitalism is that web of social and economic relationships.

The argument for socialism is not that we (who?) should replace socialism with capitalism. The argument for socialism is that capitalism will eventually fall of its own accord (with perhaps the occasional nudge here and there), and we should fill the resulting void with socialism.

So long as capitalism does not fall of (mostly) its own accord, we will have a capitalist society. However, we know that at the technological level of the railroad or higher, the capitalist class is unable to reproduce capitalism. The only reason that capitalism limped into the 21st century is that the professional-managerial class ran it for four decades. The capitalist class couldn't stand it, took back state power in 1980, and today we have Donald Trump. 'Nuff said. In the next decade (perhaps as soon as next year) everything is going to collapse 1929-style, and the PMC will be unable to save capitalism yet again.

After capitalism, we have two choices: fascism (or something very much like it) and socialism. I prefer socialism.

If you like capitalism, if it works for you, and you want to try and save it, by all means, try to save it. But I argue you should hedge your bets. If you do lose, which way do you want capitalism to fail? I urge the supporters of capitalism (who are not themselves fascists) to really see that they are doing worse by holding up socialism, not fascism, as the chief threat to capitalism.

[T]he superstition that the budget must be balanced at all times, once it is debunked, takes away one of the bulwarks that every society must have against expenditure out of control. . . . [O]ne of the functions of old-fashioned religion was to scare people by sometimes what might be regarded as myths into behaving in a way that long-run civilized life requires.

Saturday, December 23, 2017

What is socialism?

Although I am speaking generally, what follows is, and can be, only my opinion. There is no ISO committee for the definition of socialism. No matter what anyone says about socialism, a thousand other socialists will agree, and a thousand vehemently disagree.

Socialism is, first and foremost, about the working class taking and exercising political power.

Capitalism is about the capitalist class taking and exercising political power. Because the capitalist class is limited, it is, depending on how one feels about capitalists, an aristocracy or an oligarchy. How capitalism actually works is a complicated and subtle topic; its fundamental goal, however, seems clear: all power to the owners!

Economics is political: the development of capitalism opened up a new sphere of political power: the firm or factory and the manufacture of goods. Before capitalism, the land and agricultural production was the sphere of political power. Thus, socialists attend not only to the "ordinary" political sphere of individuals interacting with each other, but also to the political economy, the organization of firms and workplaces. Socialists hold that while the former is important, the latter is more important.

The parallel is not exact, but by and large capitalist firms are organized in the mode of feudal authoritarianism. There are greater and lesser individuals (CEOs) each atop a hierarchy of authority. Those below must comply absolutely* with the authority of those above; if they fail to comply, they will be punished (sacked). These feudal fiefdoms compete with one another, not on the battlefield but in the "market". For many decades, the parallel between feudalism and capitalism was even closer: firms used considerable coercion to prevent workers from leaving, rendering them the moral equivalent of serfs. The key comparison is that under feudalism, individuals owned political power; under capitalism, individuals own economic power.

*A subordinate may legitimately disagree with a superior only with the superior's permission.

There are a lot of differences between capitalism and feudalism, and no one should try to understand how capitalism works by studying feudalism. I introduce the comparison only to note that socialism rejects any form of individual power: under socialism, no individual has power; only the working class as a class has power. Socialism does not distinguish between state power (the power to directly arrest, imprison, or execute individuals) and economic power (the power to withdraw social permission to obtain the material necessities of life). Economic power rests on police power anyway: If I lose my job, have no money, and try to take the food I need to live, I will experience the pointy end of police power.

Socialism has two final goals: for workers to control firms and for workers to control the state. The workers in a firm will have democratic power over each other, and the workers in a country will have democratic power over each other, but no individual or select group will have state or economic power over other individuals.

A lot of people ask, how would this actually work? While I have some advice, the fundamental answer is that the working class must first take power; then it is they, not I, who must build socialist institutions.

What about non-workers? There are only five fundamental economic classes: owners, workers, administrators, students, and the non-productive (young children, retirees, and disabled people). Socialism proposes to eliminate only the owning class. Administrators (the civil service, the police, the army, etc.) must be politically subordinate to the working class; the rest, well, the workers will have to figure out the role of students and non-productive people; regardless of what they decide, they would have to work hard to do worse than the capitalist class.

That's really it. What the workers do with their power is up to them, not to me. As a socialist I just want to help them take power.

Socialism is, first and foremost, about the working class taking and exercising political power.

Capitalism is about the capitalist class taking and exercising political power. Because the capitalist class is limited, it is, depending on how one feels about capitalists, an aristocracy or an oligarchy. How capitalism actually works is a complicated and subtle topic; its fundamental goal, however, seems clear: all power to the owners!

Economics is political: the development of capitalism opened up a new sphere of political power: the firm or factory and the manufacture of goods. Before capitalism, the land and agricultural production was the sphere of political power. Thus, socialists attend not only to the "ordinary" political sphere of individuals interacting with each other, but also to the political economy, the organization of firms and workplaces. Socialists hold that while the former is important, the latter is more important.

The parallel is not exact, but by and large capitalist firms are organized in the mode of feudal authoritarianism. There are greater and lesser individuals (CEOs) each atop a hierarchy of authority. Those below must comply absolutely* with the authority of those above; if they fail to comply, they will be punished (sacked). These feudal fiefdoms compete with one another, not on the battlefield but in the "market". For many decades, the parallel between feudalism and capitalism was even closer: firms used considerable coercion to prevent workers from leaving, rendering them the moral equivalent of serfs. The key comparison is that under feudalism, individuals owned political power; under capitalism, individuals own economic power.

*A subordinate may legitimately disagree with a superior only with the superior's permission.

There are a lot of differences between capitalism and feudalism, and no one should try to understand how capitalism works by studying feudalism. I introduce the comparison only to note that socialism rejects any form of individual power: under socialism, no individual has power; only the working class as a class has power. Socialism does not distinguish between state power (the power to directly arrest, imprison, or execute individuals) and economic power (the power to withdraw social permission to obtain the material necessities of life). Economic power rests on police power anyway: If I lose my job, have no money, and try to take the food I need to live, I will experience the pointy end of police power.

Socialism has two final goals: for workers to control firms and for workers to control the state. The workers in a firm will have democratic power over each other, and the workers in a country will have democratic power over each other, but no individual or select group will have state or economic power over other individuals.

A lot of people ask, how would this actually work? While I have some advice, the fundamental answer is that the working class must first take power; then it is they, not I, who must build socialist institutions.

What about non-workers? There are only five fundamental economic classes: owners, workers, administrators, students, and the non-productive (young children, retirees, and disabled people). Socialism proposes to eliminate only the owning class. Administrators (the civil service, the police, the army, etc.) must be politically subordinate to the working class; the rest, well, the workers will have to figure out the role of students and non-productive people; regardless of what they decide, they would have to work hard to do worse than the capitalist class.

That's really it. What the workers do with their power is up to them, not to me. As a socialist I just want to help them take power.

Sunday, December 17, 2017

Friedman on Libertarianism

In his critique of libertarianism [PDF; link fixed], Jeffrey Friedman (1997) argues that libertarianism can be justified either morally or consequentially and that libertarian advocates fail to do either. I don't want to summarize Friedman's argument except to say that he uses almost 60 pages to fault the logical arguments for libertarianism as circular and the empirical arguments as unevidenced. I agree with both of Friedman's points, and I've written on them extensively myself. Rather, I want to examine two essays critical of Friedman's arguments.

Tom G. Palmer (1998) spends several pages establishing that libertarianism must be justified consequentially; he denies that libertarianism is an a priori truth or categorical imperative. However, he does not, as the alert reader might expect, then turn to making an actual consequentialist or utilitarian argument for libertarianism. Palmer asserts (mistakenly, I think) that Friedman demands an impossibly high standard of proof. But in rebuttal, Palmer fails to offer any sort of evidence. If an author argues for an alternative standard of proof — and his standard is reasonable — then I expect evidence meeting the alternative standard. Palmer fails to even cite any empirical justification for libertarianism. I'm not saying such evidence does not exist, but I have degrees in both political science and economics, and I know the empirical case for libertarianism is not common knowledge in these disciplines; if the evidence is there, show me.

Instead, Palmer focuses on Friedman's supposed errors of logic. Palmer first faults Friedman's definition of "freedom". But Palmer does not seem to understand Friedman's argument, that by definition, all rules of behavior coercively take away some rights. Palmer's counterexample does not address Friedman's argument:

Palmer quotes Algernon Sidney's (1990) definition of liberty, which "solely consists of in an independency upon the will of another" (p. 346; emphasis added) and quotes Locke at greater length in the same vein. Even if we are to accept that there is no "natural" right for one person to impose their will on another by violence, for a person to do whatever else they like seems to be identical with being independent of another's will. Alas, Palmer does not make any explicit connection between this rather banal definition to libertarian philosophy. The quoted passage of Locke seems to suborn some degree of interventionism: Locke asserts that disposing of one's property "within the Allowance of those Laws under which he is" (qtd. in Palmer 1998, p. 346) does not compromise liberty. Thus, it is unclear how Palmer would differentiate libertarianism from ordinary liberalism.

Palmer continues with a disquisition on morality in which I can see neither a substantive criticism of Friedman nor illumination of libertarianism, and closes with a few trivial quibbles. Nowhere in his response does he engage with either of Friedman's claims, regarding the circularity of the libertarian moral argument or the lack of evidence for the empirical argument.

J. C. Lester at least admits that many libertarians make deficient a priori arguments. He makes an argument similar to Palmer's for a reasonable empirical standard of evidence. And then, like Palmer, fails to offer any, handwaving vaguely that "libertarians have read of research and economic theory that appear to refute all the assertions that the state is the solution, rather than the problem" (p. 2; emphasis added). Again, this research and economic theory is not common knowledge in academia, and the lack of specifics fails to persuade. (There is evidence and theory that some kinds of state interventions do more harm than good, but there's a lot of evidence and theory that other kinds of state intervention are not only useful but seem indispensable.) And, like Palmer, Lester immediately switches to arguments that are meaningful only in an a priori context.

Lester argues that the true essence of libertarianism is "the absence of proactive impositions," which he claims is "what libertarians intuitively grasp" (p. 3). In addition to the question of whether this absence is morally or empirically justified, Lester's formulation suffers from the defect that not only do I not understand it at all, Lester himself does not understand it clearly: he admits that he cannot say it is "perspicuously clear and without philosophical problems" (p. 3). Indeed.

If you're going to make an a priori case, make it. If a person criticizes the a priori case, it is not enough to simply say they have misunderstood or made a logical error, even if such an assertion is true. You still have to go over the original argument and show me not that the criticism is bad but that the original argument survives the criticism.

As to the evidentiary case, when evidence is common knowledge (as with evolution or anthropogenic climate change), it is not unjustified to say so, and direct readers to the appropriate evidence. But the empirical evidence for libertarianism is not common knowledge, even in academia. So show me. I'm happy to apply an ordinarily scientific interpretation of the evidence: I do not expect perfection, but I insist on good enough.

References

Friedman, Jeffrey (1997). What's wrong with libertarianism. Critical Review 11.3: 407-467. doi: 10.1080/08913819708443469

Lester. J. C. (2012). What's wrong with "What's wrong with libertarianism": A reply to Jeffrey Friedman. Academia.edu

Palmer, Tom G. (1998). What's not wrong with libertarianism: Reply to Friedman. Critical Review 12.3: 337-358. doi: 10.1080/08913819808443507

Tom G. Palmer (1998) spends several pages establishing that libertarianism must be justified consequentially; he denies that libertarianism is an a priori truth or categorical imperative. However, he does not, as the alert reader might expect, then turn to making an actual consequentialist or utilitarian argument for libertarianism. Palmer asserts (mistakenly, I think) that Friedman demands an impossibly high standard of proof. But in rebuttal, Palmer fails to offer any sort of evidence. If an author argues for an alternative standard of proof — and his standard is reasonable — then I expect evidence meeting the alternative standard. Palmer fails to even cite any empirical justification for libertarianism. I'm not saying such evidence does not exist, but I have degrees in both political science and economics, and I know the empirical case for libertarianism is not common knowledge in these disciplines; if the evidence is there, show me.

Instead, Palmer focuses on Friedman's supposed errors of logic. Palmer first faults Friedman's definition of "freedom". But Palmer does not seem to understand Friedman's argument, that by definition, all rules of behavior coercively take away some rights. Palmer's counterexample does not address Friedman's argument:

If that were true, then using force to prevent another person from having sexual congress with yourself . . . would be just as much a use of force as is using force to have sexual congress with another person. Therefore there must be no difference between the two, at least with respect to whether one approach is more or less coercive or free than the other.But this is true. Both rape and resisting (or punishing) rape are equally coercive. It is just that socially, we have constructed the standard that coercion is justified in the former case and not justified in the second case. I will reiterate the point I've made many times before: the libertarian's moral case always seems to be that coercion for things they don't like is wrong because it is coercive, and coercion for things they do like is not coercion because it is for what they like.

Palmer quotes Algernon Sidney's (1990) definition of liberty, which "solely consists of in an independency upon the will of another" (p. 346; emphasis added) and quotes Locke at greater length in the same vein. Even if we are to accept that there is no "natural" right for one person to impose their will on another by violence, for a person to do whatever else they like seems to be identical with being independent of another's will. Alas, Palmer does not make any explicit connection between this rather banal definition to libertarian philosophy. The quoted passage of Locke seems to suborn some degree of interventionism: Locke asserts that disposing of one's property "within the Allowance of those Laws under which he is" (qtd. in Palmer 1998, p. 346) does not compromise liberty. Thus, it is unclear how Palmer would differentiate libertarianism from ordinary liberalism.

Palmer continues with a disquisition on morality in which I can see neither a substantive criticism of Friedman nor illumination of libertarianism, and closes with a few trivial quibbles. Nowhere in his response does he engage with either of Friedman's claims, regarding the circularity of the libertarian moral argument or the lack of evidence for the empirical argument.

J. C. Lester at least admits that many libertarians make deficient a priori arguments. He makes an argument similar to Palmer's for a reasonable empirical standard of evidence. And then, like Palmer, fails to offer any, handwaving vaguely that "libertarians have read of research and economic theory that appear to refute all the assertions that the state is the solution, rather than the problem" (p. 2; emphasis added). Again, this research and economic theory is not common knowledge in academia, and the lack of specifics fails to persuade. (There is evidence and theory that some kinds of state interventions do more harm than good, but there's a lot of evidence and theory that other kinds of state intervention are not only useful but seem indispensable.) And, like Palmer, Lester immediately switches to arguments that are meaningful only in an a priori context.

Lester argues that the true essence of libertarianism is "the absence of proactive impositions," which he claims is "what libertarians intuitively grasp" (p. 3). In addition to the question of whether this absence is morally or empirically justified, Lester's formulation suffers from the defect that not only do I not understand it at all, Lester himself does not understand it clearly: he admits that he cannot say it is "perspicuously clear and without philosophical problems" (p. 3). Indeed.

If you're going to make an a priori case, make it. If a person criticizes the a priori case, it is not enough to simply say they have misunderstood or made a logical error, even if such an assertion is true. You still have to go over the original argument and show me not that the criticism is bad but that the original argument survives the criticism.

As to the evidentiary case, when evidence is common knowledge (as with evolution or anthropogenic climate change), it is not unjustified to say so, and direct readers to the appropriate evidence. But the empirical evidence for libertarianism is not common knowledge, even in academia. So show me. I'm happy to apply an ordinarily scientific interpretation of the evidence: I do not expect perfection, but I insist on good enough.

References

Friedman, Jeffrey (1997). What's wrong with libertarianism. Critical Review 11.3: 407-467. doi: 10.1080/08913819708443469

Lester. J. C. (2012). What's wrong with "What's wrong with libertarianism": A reply to Jeffrey Friedman. Academia.edu

Palmer, Tom G. (1998). What's not wrong with libertarianism: Reply to Friedman. Critical Review 12.3: 337-358. doi: 10.1080/08913819808443507

Saturday, November 25, 2017

Classes as social relations

A class in the Marxian sense consists of people who are embedded in certain kinds of social relations. Briefly, capitalists are those who engage in M-C-M* economic relationships, turning money into commodities into more money; Marx holds that the M*, more money after commodity relations, consists of the surplus value of labor expropriated from the workers. Workers engage in C-M-C economic relationships. They sell a commodity (their labor power) to the capitalists, receive money, which they then use to buy the stuff they need to live.

But there are other social relations necessary to maintain a society. These relations are not productive, they are reproductive. (There are also parasitic social relations, which are neither productive nor reproductive.) The modern (19th and early 20th century) academic system was not productive. Knowledge and culture are not something produced in the Marxian sense because knowledge and culture are not consumed in the sense that an ordinary television show is consumed, i.e. used up. People get tired of even classics like M*A*S*H or a magazine article about bees (so this is ordinary production), but people will never get tired of the Iliad nor the Theory of General Relativity. More importantly, reproduction needs to happen regardless of whether it can be made even temporarily profitable.

Hence I define the professional-managerial class not in terms of the tools it uses, but in terms of their social relations of reproduction.

Hence I view the class analysis of the 20th century broadly thus: during the Great Depression, the PMC as a reproductive class seizes state power in 1933. Any economic ruling class must have a countervailing reproductive class to both legitimize the authority of the ruling class and to prevent the ruling class from destroying society. Such was the role of the Church in the Middle Ages. (Both Augustine and Aquinas, for example, have much to say about secular state legitimacy.)

The capitalist class, as soon the immediate crisis has stabilized, began its project to retake state power. The capitalist class directly undermined the legitimacy of the PMC as elitist*, effeminate**, and race traitors. They co-opt the institutions (academic science and humanities, journalism, "high" culture, primary and secondary education) the PMC used to reproduce capitalist society, turning them into productive rather than reproductive institutions. They co-opted the leaders of the PMC, turning them directly into capitalists or ensuring they slavishly submitted to the capitalist class (e.g. most academic economists), abandoning the second half of their role as critics and moderators

*Never mind that the capitalist class is far more elitist than the PMC ever was or could be.

**<sarcasm> Women can't rule, n'est ce pas?, except in the exceptional case where they almost perfectly imitate men. </sarcasm>

In 1980, the capitalist class retook state power, but they were not content. Unlike the PMC, the capitalists understood that the capitalists and the PMC were enemies, and reading Machiavelli, they knew that one's enemies must be utterly destroyed. So the capitalists have continued to undermine the PMC; they will not stop until there is no such thing as a professional-managerial class as a class, only individual professionals and managers directly subordinate to individual capitalists and completely subservient to the capitalist class.

One of my main themes has been criticism of the Democratic party. I see the Democratic party not as the party of those who control information, but as the party that still tries to restore the PMC to state power. Or, more precisely, Democratic voters — aside from middle-class white women who (justly) want to preserve their access to legal abortion and minorities who (justly) fear that the Republican party will enslave or just murder them all — are those who want to return to the days when the PMC as a class held and exercised state power. I believe these voters are fundamentally mistaken. The PMC cannot regain state power; the best they can do is operate a fighting retreat, slowing the capitalists' destruction of society.

Dustin makes an important point in his comment:

I agree completely that information has become the critical basis of power. However, the way that those who control information have used it fundamentally shifted only in the early 21st century, decades after the capitalists regained state power. The key is to make all information Marxian commodities, and place all of information production under capitalist commodity relations (M-C-M*), with knowledge producers as workers, not a separate reproductive class.

I really want to stress that what capitalists own (factories, money and financial flows, information) is less important than how they own it, i.e. the social relations.

But there are other social relations necessary to maintain a society. These relations are not productive, they are reproductive. (There are also parasitic social relations, which are neither productive nor reproductive.) The modern (19th and early 20th century) academic system was not productive. Knowledge and culture are not something produced in the Marxian sense because knowledge and culture are not consumed in the sense that an ordinary television show is consumed, i.e. used up. People get tired of even classics like M*A*S*H or a magazine article about bees (so this is ordinary production), but people will never get tired of the Iliad nor the Theory of General Relativity. More importantly, reproduction needs to happen regardless of whether it can be made even temporarily profitable.

Hence I define the professional-managerial class not in terms of the tools it uses, but in terms of their social relations of reproduction.

Hence I view the class analysis of the 20th century broadly thus: during the Great Depression, the PMC as a reproductive class seizes state power in 1933. Any economic ruling class must have a countervailing reproductive class to both legitimize the authority of the ruling class and to prevent the ruling class from destroying society. Such was the role of the Church in the Middle Ages. (Both Augustine and Aquinas, for example, have much to say about secular state legitimacy.)

The capitalist class, as soon the immediate crisis has stabilized, began its project to retake state power. The capitalist class directly undermined the legitimacy of the PMC as elitist*, effeminate**, and race traitors. They co-opt the institutions (academic science and humanities, journalism, "high" culture, primary and secondary education) the PMC used to reproduce capitalist society, turning them into productive rather than reproductive institutions. They co-opted the leaders of the PMC, turning them directly into capitalists or ensuring they slavishly submitted to the capitalist class (e.g. most academic economists), abandoning the second half of their role as critics and moderators

*Never mind that the capitalist class is far more elitist than the PMC ever was or could be.

**<sarcasm> Women can't rule, n'est ce pas?, except in the exceptional case where they almost perfectly imitate men. </sarcasm>

In 1980, the capitalist class retook state power, but they were not content. Unlike the PMC, the capitalists understood that the capitalists and the PMC were enemies, and reading Machiavelli, they knew that one's enemies must be utterly destroyed. So the capitalists have continued to undermine the PMC; they will not stop until there is no such thing as a professional-managerial class as a class, only individual professionals and managers directly subordinate to individual capitalists and completely subservient to the capitalist class.

One of my main themes has been criticism of the Democratic party. I see the Democratic party not as the party of those who control information, but as the party that still tries to restore the PMC to state power. Or, more precisely, Democratic voters — aside from middle-class white women who (justly) want to preserve their access to legal abortion and minorities who (justly) fear that the Republican party will enslave or just murder them all — are those who want to return to the days when the PMC as a class held and exercised state power. I believe these voters are fundamentally mistaken. The PMC cannot regain state power; the best they can do is operate a fighting retreat, slowing the capitalists' destruction of society.

Dustin makes an important point in his comment:

My theory as a whole is that some time in the early 20th century, control over information and its dissemination actually "passed up" control over capital in being the determinant of who holds the power. Improvements in print press technology combined with the invention/improvements of radio and eventually even early forms of television in the late 1800s & early 1900s enabled for the first time in history the creation of a true mass-media and other organs of true mass-dissemination of information (and misinformation).

I think that this is what actually led to the PMC wresting of power from the capitalists in the early 20th century. The PMC were always the traditional "dealers" in media, journalism, etc., so the elite of the PMC were uniquely seated to benefit from this vast technological shift.

I agree completely that information has become the critical basis of power. However, the way that those who control information have used it fundamentally shifted only in the early 21st century, decades after the capitalists regained state power. The key is to make all information Marxian commodities, and place all of information production under capitalist commodity relations (M-C-M*), with knowledge producers as workers, not a separate reproductive class.

I really want to stress that what capitalists own (factories, money and financial flows, information) is less important than how they own it, i.e. the social relations.

Friday, November 24, 2017

Class structuralism

To an extent, people in the PMC were assholes. First, they are an elite, and people in any elite are elitist. They really do think they're better than the masses. Criticizing an elite for thinking they're better is like criticizing the rich for thinking he has more money than the poor. Of course elites think they're better than the masses — that's the whole point of being among the elite — and when pressed, they would answer, "Yes, I think I'm better than you because I am better than you: I'm smarter, better educated, and more cultured. Me and my friends are running the world because we can run it better than you can."

The point is not whether they are correct about actually being better (they're not); the point is that criticizing people just because they do something they believe is right as if it were obviously wrong is not only ineffective but counterproductive.

(It's not counterproductive per se if the goal is to simply express one's personal animosity, but it's certainly ineffective when spoken to me personally because I don't really care about others' (not even my friends') personal animosities: work it out; don't drag me into it.)

This criticism is counterproductive because if the goal is to stop the elite from holding the masses in contempt, the charge that they think they're better than us just makes them feel more contemptuous. If the goal is anti-elitism, I think we have to be careful to criticize elites in such a way that their collapse helps the cause of true democracy and anti-elitism. If we criticize an elite the wrong way, they just collapse on the masses, paving the way for a new, worse, elite.

Marx, for example, is careful to avoid personal criticism of the bourgeoisie.

But [in Capital] individuals are dealt with only in so far as they are the personifications of economic categories, embodiments of particular class relations and class-interests. My standpoint, from which the evolution of the economic formation of society is viewed as a process of natural history, can less than any other make the individual responsible for relations whose creature he socially remains, however much he may subjectively raise himself above them.*Marx has a reason for this view: he wants to avoid the claim (made, I think, by many utopian socialists) is that society is bad simply because bad people happen to be in control; if we could put good people in positions of control, everything would be fine. Marx argues instead that the people don't drive the system; the system drives the people. Capitalists are "bad" because the system forces them to be bad. (More precisely, I think capitalism mostly selects for bad people to acquire power.) Madison opined,

If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.The problem is not with the people, it is with the system. I think both Marx and Madison would agree at least that we must turn our attention to the structures and institutions of society, not to the personal failings of the people in those institutions, and certainly not to the failings that the system imposes on them.

Hence my continuing discussion of the role of the PMC in the capitalist system and the history of the struggle between the PMC and the capitalist class. The capitalist class has undertaken a project of delegitimizing the PMC. To simply concur with their delegitimation is to mistake the enemy of my enemy as my friend. To just delegitimize the PMC without also delegitimize capitalist class (more than just an aside that the capitalists are assholes too) is to simply remove an obstacle to the capitalists' project to gain absolute power. The success of this project is probably guaranteed (if it has not actually succeeded), and that capitalists' absolute power will be their undoing, but those are not good reasons to endorse or assist their project.

I think good socialists should want for the capitalist system to fail gracefully into socialism. I don't think that will actually happen: I think the path is laissez faire capitalism to some sort of fascist-like authoritarianism to socialism (always under the threat of annihilation), but how it will or might happen is a secondary concern. The primary concern should be, I think, to position socialism to pick up the pieces as soon as possible, which requires gaining ideological trust. Even if the capitalist system really does fail catastrophically, being seen to endorse, cooperate, or even just unwittingly assist with catastrophe does not inspire trust.

I too want to delegitimize the PMC, but I want them to fall on the capitalists, not on the masses. To simply say that they are arrogant know-it-alls is to implicitly endorse the capitalist ideology that capitalists earn their right to rule by their productive success and that the PMC, with their impossible ideas, highfalutin jargon, and effeminate* morality, acts as an obstacle to their deserved power. Instead, I damn the PMC not for opposing capitalism but for failing to oppose capitalism more directly, even as the capitalist class plots the extinction of the PMC. They failed to protect the masses, but worse yet, they failed to protect themselves. The workers cannot depend on the PMC in their struggle against capitalism; they must take up the struggle themselves.

*I am using "effeminate" because that's clearly the thrust of the capitalist class's criticism of anti-racism, feminism, and equality of orientation. Capitalists are very patriarchal.

Monday, November 20, 2017

Personal Statements

Harry Brighouse gives good advice on writing personal statements for graduate school applications. In short, he observes that personal statements are rarely if ever decisive for acceptance. So don't spend too much time on it, it's all right to be ordinary, and just answer the questions.

In philosophy the main purpose of the personal statement is to convey that you know what you are doing, that you are genuinely interested in the program you’re applying to, and that you are not a complete flake.

Saturday, August 12, 2017

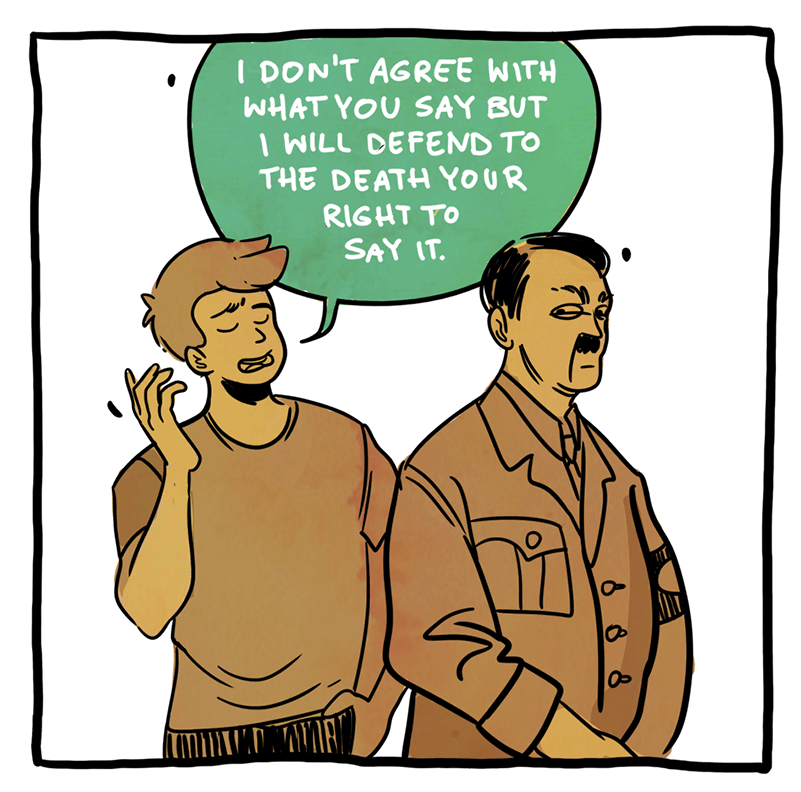

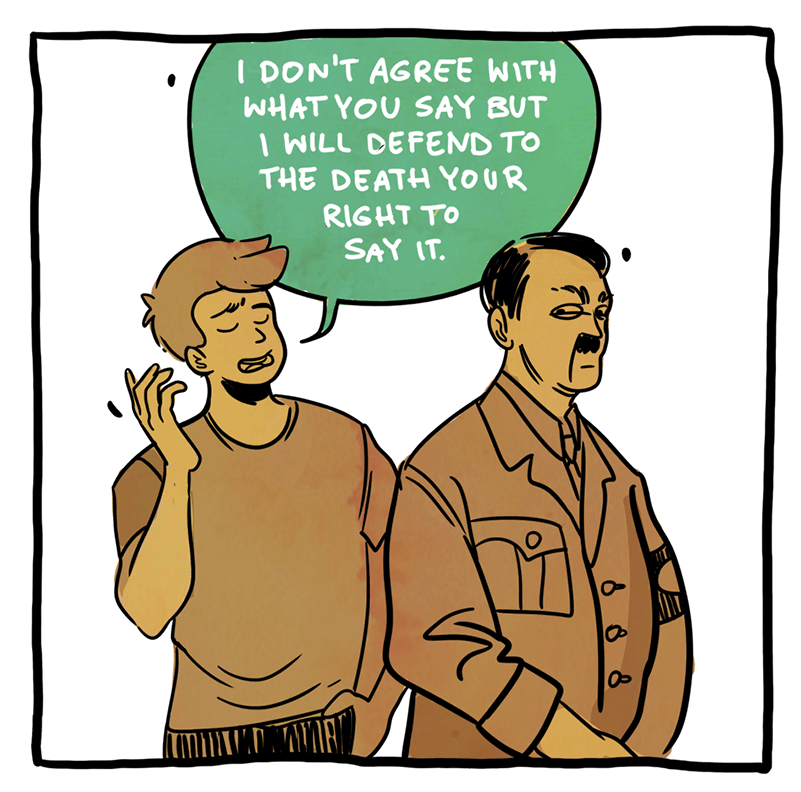

Defending racism

I have to ask, is defending racism (and sexism, religious bigotry, etc. ad nauseam; all the arguments here apply mutatis mutandis to other forms of discrimination), even if not in substance but only procedurally, the hill that liberals want to die on? Should we extend the most robust free speech protection to racists?

As far as I know, the state has not in recent memory put anyone in jail, has not fined anyone, has not permitted anyone to be sued in civil court, has not used any direct state power to punish anyone for racist speech. The state has not disbanded or punished any organization, publication, or association for racist speech, or forbidden any organization to publish racist speech. And, as far as I know, any demand for such state suppression of racist speech has been with nothing more than bemused refusal. I think the state shouldn't do these things, and they seem to agree: they're not doing these things. So, strictly speaking, racist speech is just not a First Amendment issue.

However, the "hammer of the state" is not the only form of coercion. Employers can coerce their employees by threatening to fire them and would-be employees by refusing to hire them. Universities can coerce students by suspending them, expelling them, altering their grades, or refusing to graduate them. A social group can expel or shame a member. I can coerce my friends by threatening to withhold my friendship. (I've done so, unapologetically: there are some views that disqualify someone from my good opinion, regardless of their other qualities). I disagree with how coercion is structured, but I am not an anarchist: I do not argue for the abolition of structures of coercion, but for the establishment of different structures. But that's an argument for another day. Our liberal democratic-republic capitalist has set up these structures of coercion, so how should we use them? Should we use the actually existing non-state structures of coercion against racism?

Any time we employ coercion, we will ruin some people's lives. That's the whole point: if you do X, we'll ruin your life, so don't fucking do it. I don't think anyone has actually starved to death because they've been denied employment for racist speech, but I'm sure that some people have been relegated to the hell of low-wage employment that liberal democratic-republican capitalism has set up to punish deviants.

The state itself should not regulate the "marketplace of ideas" (beyond the usual prohibitions of libel, slander, incitement to riot, conspiracy, and treason), but that doesn't mean that the marketplace should be absolutely free. To extend the metaphor, the marketplace of ideas requires an "entry fee", especially when we're talking about ideas in academia, because the intellectual function of academia is to legitimize ideas. And the entry fee is that you have to establish at least a foothold of evidence and argument.

Because we are a society founded on slavery, we grandfathered in racism. Academia has exhaustively examined the idea of racism. And we have found that not only is racism oppressive, it is absolutely, completely, thoroughly, totally, without intellectual and evidentiary merit. It has not paid the entry fee, and thus does not deserve inclusion in the marketplace of ideas. Racism not does not deserve (further) critical inquiry because there is literally nothing there to critically engage with, just a steaming mound of fetid horseshit.

And, because racism is actually oppressive, racist speech should not only be excluded, but actively punished.

So too for sexism, for homophobia, for transphobia, for religious bigotry. These are not even ideas, these are just ignorant superstitions, without a shred of intellectual merit. If someone holds these ideas, he or she should express them only with the blinds closed. Say them in public, and they should be well and truly fucked in civilized society.

If that makes me a heretic against liberalism, well, I'm not a liberal, I'm a communist. If the liberal ideal of free speech requires giving a free hand to racist assholes, who want drive people of color off campus and out of good jobs, to drive them out of the labor aristocracy, the professional-managerial class, and the capitalist class and confine them to the exploited working class, then liberals can go fuck themselves.

As far as I know, the state has not in recent memory put anyone in jail, has not fined anyone, has not permitted anyone to be sued in civil court, has not used any direct state power to punish anyone for racist speech. The state has not disbanded or punished any organization, publication, or association for racist speech, or forbidden any organization to publish racist speech. And, as far as I know, any demand for such state suppression of racist speech has been with nothing more than bemused refusal. I think the state shouldn't do these things, and they seem to agree: they're not doing these things. So, strictly speaking, racist speech is just not a First Amendment issue.

However, the "hammer of the state" is not the only form of coercion. Employers can coerce their employees by threatening to fire them and would-be employees by refusing to hire them. Universities can coerce students by suspending them, expelling them, altering their grades, or refusing to graduate them. A social group can expel or shame a member. I can coerce my friends by threatening to withhold my friendship. (I've done so, unapologetically: there are some views that disqualify someone from my good opinion, regardless of their other qualities). I disagree with how coercion is structured, but I am not an anarchist: I do not argue for the abolition of structures of coercion, but for the establishment of different structures. But that's an argument for another day. Our liberal democratic-republic capitalist has set up these structures of coercion, so how should we use them? Should we use the actually existing non-state structures of coercion against racism?

Any time we employ coercion, we will ruin some people's lives. That's the whole point: if you do X, we'll ruin your life, so don't fucking do it. I don't think anyone has actually starved to death because they've been denied employment for racist speech, but I'm sure that some people have been relegated to the hell of low-wage employment that liberal democratic-republican capitalism has set up to punish deviants.

The state itself should not regulate the "marketplace of ideas" (beyond the usual prohibitions of libel, slander, incitement to riot, conspiracy, and treason), but that doesn't mean that the marketplace should be absolutely free. To extend the metaphor, the marketplace of ideas requires an "entry fee", especially when we're talking about ideas in academia, because the intellectual function of academia is to legitimize ideas. And the entry fee is that you have to establish at least a foothold of evidence and argument.

Because we are a society founded on slavery, we grandfathered in racism. Academia has exhaustively examined the idea of racism. And we have found that not only is racism oppressive, it is absolutely, completely, thoroughly, totally, without intellectual and evidentiary merit. It has not paid the entry fee, and thus does not deserve inclusion in the marketplace of ideas. Racism not does not deserve (further) critical inquiry because there is literally nothing there to critically engage with, just a steaming mound of fetid horseshit.

And, because racism is actually oppressive, racist speech should not only be excluded, but actively punished.

So too for sexism, for homophobia, for transphobia, for religious bigotry. These are not even ideas, these are just ignorant superstitions, without a shred of intellectual merit. If someone holds these ideas, he or she should express them only with the blinds closed. Say them in public, and they should be well and truly fucked in civilized society.

If that makes me a heretic against liberalism, well, I'm not a liberal, I'm a communist. If the liberal ideal of free speech requires giving a free hand to racist assholes, who want drive people of color off campus and out of good jobs, to drive them out of the labor aristocracy, the professional-managerial class, and the capitalist class and confine them to the exploited working class, then liberals can go fuck themselves.

Saturday, August 05, 2017

The detective

In everything that can be called art there is a quality of redemption. It may be pure tragedy, if it is high tragedy, and it may be pity and irony, and it may be the raucous laughter of the strong man. But [in a detective novel] down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. The detective in this kind of story must be such a man. He is the hero, he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor, by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it. He must be the best man in his world and a good enough man for any world. I do not care much about his private life; he is neither a eunuch nor a satyr; I think he might seduce a duchess and I am quite sure he would not spoil a virgin; if he is a man of honor in one thing, he is that in all things. He is a relatively poor man, or he would not be a detective at all. He is a common man or he could not go among common people. He has a sense of character, or he would not know his job. He will take no man’s money dishonestly and no man’s insolence without a due and dispassionate revenge. He is a lonely man and his pride is that you will treat him as a proud man or be very sorry you ever saw him. He talks as the man of his age talks, that is, with rude wit, a lively sense of the grotesque, a disgust for sham, and a contempt for pettiness. The story is his adventure in search of a hidden truth, and it would be no adventure if it did not happen to a man fit for adventure. He has a range of awareness that startles you, but it belongs to him by right, because it belongs to the world he lives in.

If there were enough like him, I think the world would be a very safe place to live in, and yet not too dull to be worth living in.

-- Raymond Chandler, The Simple Art of Murder

Wednesday, August 02, 2017

Why the democrats cannot be progressive

Color me unsurprised: Dem campaign chief vows no litmus test on abortion, via PZ Myers, who says,

We tried this once. In the early 1930s, the rich people lost all their money. The professional-managerial class stepped in, took state power, and fixed the economy by actually giving money to poor people. The PMC made it very difficult for the capitalist class to get their money back and restore their relative economic power. The PMC has made a lot of egregious mistakes, especially the Vietnam war, but it's pretty clear that the capitalist class is utterly incompetent at political rule and cannot manage a national economy more complicated than that of the 1820s, much less a global economy.

But they did not destroy the capitalist class. Both Lenin and Mao discovered that destroying the capitalist class is a very difficult task, which they failed to complete.

It might have been possible to destroy the capitalist class in an already-industrialized country such as the United States, but again, as we saw in mid 19th-century Europe, that too is a difficult task: the capitalist class has a lot of power and no scruples: they're willing to kill hundreds of millions of people not only to keep their power but also just to make an extra buck. How do honest, moral revolutionaries confront such monstrosity without becoming monsters ourselves?

So one cannot really blame the PMC for blinking. They thought they could make a deal with the capitalists: let us run the state, do what needs to be done to keep the economy from failing and the people from revolting, and you get to keep running the businesses, make reasonable money, and live in comfort. Faced with an angry mob whom the capitalists feared might take up torches and pitchforks, the capitalists agreed, but when the mob dispersed, the capitalist class was having none of it. They didn't want to suffer egregious oppression under the boot-heels of the professional-managerial class: they wanted their money back. All of it. And more. And they'll get it.

Both the Democrats and Republicans were caught off-guard by Trump and Sanders. Trump won the Republican nomination because the Republicans knew he wouldn't get in the way of the capitalist agenda; Sanders lost precisely because he would have been a little bit progressive, and the capitalist class would not stand for it. But they didn't take Sanders seriously enough early enough, and he got close to winning the Democratic nomination; he might have defeated Trump. The capitalist class will not make the same mistake twice, and the Democratic party is eagerly helping, pushing the line that socialism is sexist and racist.

The professional-managerial class — and the PMC's Democratic party — still cannot comprehend that the capitalist class wants all the power, no matter and damn the consequences. Fiat justitia ruat cælum. The PMC keeps making concessions to the capitalist class, but the capitalists don't want a bigger piece of the pie, they want to be the ones cutting the pie and handing out slices.

But why should we expect Democrats to comprehend the capitalist class's will to power? There are only two alternatives — give up and commit political suicide or foment revolution — both unthinkable to those who have more than a minimal stake in the system. (It's easy for me to contemplate revolution; I have nothing to lose either way: I'll be dead before the capitalists completely ruin the university system.)

The Democratic party as an organ of the PMC died with the election of Trump. The professional-managerial class will never wield any political or economic power, and the Democratic party will probably be tasked with destroying the intellectual and political legitimacy of socialism. But even the slightly less assholy capitalists are still politically and macroeconomically incompetent, and they are about to crash the global economy so hard that the global financial crisis and lesser depression of 2007 to present, the Long Depression, even the Great Depression look like mild downturns. The capitalist class knows their enemy, and they will not allow the professional-managerial class to save them from themselves.

So everything is about to collapse, the relatively smart and well-educated people in the PMC can neither halt nor help recover from the collapse. Marx's prediction is about to become true: society will become divided between the capitalist class (and their now-subservient minions in the PMC) and the working class.

However, the working class can be dominated, at least for a while. They will go to war and die by the millions, tolerate near-starvation, material deprivation, and disease, they will submit to the most brutal authoritarian rule. Remember that the German people never revolted against the Nazis, and that even after the most brutal deprivation, the Bolsheviks took power only because of Lenin's intellect and will; without Lenin himself, Russia would have devolved into chaos. (Mao is a little more complicated.)

And we probably will. After Trump, le déluge. I am completely convinced that the Sanders-Warren wing of the Democratic party that is at least condescendingly charitable towards the working class has zero chance of taking state power after Trump (or Pence, if Trump resigns or is impeached and convicted). Regardless of who is president, we will have a capitalist Republican Congress, and a majority of Republican state governments; the president will either be a Republican or an ineffectual Democrat. Just a few more Republican (or Blue Dog Democratic) state governments and the capitalist class can amend the Constitution; they will be sure to do so. (See e.g. Hungary.)

We will have a wave of nationalistic patriotism supporting some big war, perhaps against the Middle East, perhaps against Russia. We will have food rationing, gas rationing, medical rationing, and the working class will tolerate it. At least for a while. No one can predict what will happen then: we could all die, a socialist utopia might emerge, or anything in between.

I have this crazy idea that America really needs a political party that supports labor, women, and minorities, and that is dedicated to helping all people rise up. It should favor causes that improve civil rights and distributes power widely and works on making America better, rather than claiming it is already the best. It ought to have a platform that states clearly that it wants to promote the general welfare and strengthens every level of society, and that encourages greater autonomy of individuals, no matter how poor or wealthy they are. [emphasis added]Sadly, it really is a crazy idea, mostly because of the emphasized passage above. The fundamental rule of capitalism is don't fuck with rich people's money. Don't take it, don't tax it, don't fine them. Don't enact policies that will substantially transfer income or wealth to the undeserving poor (i.e. not obscenely rich).

We tried this once. In the early 1930s, the rich people lost all their money. The professional-managerial class stepped in, took state power, and fixed the economy by actually giving money to poor people. The PMC made it very difficult for the capitalist class to get their money back and restore their relative economic power. The PMC has made a lot of egregious mistakes, especially the Vietnam war, but it's pretty clear that the capitalist class is utterly incompetent at political rule and cannot manage a national economy more complicated than that of the 1820s, much less a global economy.

But they did not destroy the capitalist class. Both Lenin and Mao discovered that destroying the capitalist class is a very difficult task, which they failed to complete.

It might have been possible to destroy the capitalist class in an already-industrialized country such as the United States, but again, as we saw in mid 19th-century Europe, that too is a difficult task: the capitalist class has a lot of power and no scruples: they're willing to kill hundreds of millions of people not only to keep their power but also just to make an extra buck. How do honest, moral revolutionaries confront such monstrosity without becoming monsters ourselves?

So one cannot really blame the PMC for blinking. They thought they could make a deal with the capitalists: let us run the state, do what needs to be done to keep the economy from failing and the people from revolting, and you get to keep running the businesses, make reasonable money, and live in comfort. Faced with an angry mob whom the capitalists feared might take up torches and pitchforks, the capitalists agreed, but when the mob dispersed, the capitalist class was having none of it. They didn't want to suffer egregious oppression under the boot-heels of the professional-managerial class: they wanted their money back. All of it. And more. And they'll get it.

Both the Democrats and Republicans were caught off-guard by Trump and Sanders. Trump won the Republican nomination because the Republicans knew he wouldn't get in the way of the capitalist agenda; Sanders lost precisely because he would have been a little bit progressive, and the capitalist class would not stand for it. But they didn't take Sanders seriously enough early enough, and he got close to winning the Democratic nomination; he might have defeated Trump. The capitalist class will not make the same mistake twice, and the Democratic party is eagerly helping, pushing the line that socialism is sexist and racist.

The professional-managerial class — and the PMC's Democratic party — still cannot comprehend that the capitalist class wants all the power, no matter and damn the consequences. Fiat justitia ruat cælum. The PMC keeps making concessions to the capitalist class, but the capitalists don't want a bigger piece of the pie, they want to be the ones cutting the pie and handing out slices.

But why should we expect Democrats to comprehend the capitalist class's will to power? There are only two alternatives — give up and commit political suicide or foment revolution — both unthinkable to those who have more than a minimal stake in the system. (It's easy for me to contemplate revolution; I have nothing to lose either way: I'll be dead before the capitalists completely ruin the university system.)

The Democratic party as an organ of the PMC died with the election of Trump. The professional-managerial class will never wield any political or economic power, and the Democratic party will probably be tasked with destroying the intellectual and political legitimacy of socialism. But even the slightly less assholy capitalists are still politically and macroeconomically incompetent, and they are about to crash the global economy so hard that the global financial crisis and lesser depression of 2007 to present, the Long Depression, even the Great Depression look like mild downturns. The capitalist class knows their enemy, and they will not allow the professional-managerial class to save them from themselves.

So everything is about to collapse, the relatively smart and well-educated people in the PMC can neither halt nor help recover from the collapse. Marx's prediction is about to become true: society will become divided between the capitalist class (and their now-subservient minions in the PMC) and the working class.

However, the working class can be dominated, at least for a while. They will go to war and die by the millions, tolerate near-starvation, material deprivation, and disease, they will submit to the most brutal authoritarian rule. Remember that the German people never revolted against the Nazis, and that even after the most brutal deprivation, the Bolsheviks took power only because of Lenin's intellect and will; without Lenin himself, Russia would have devolved into chaos. (Mao is a little more complicated.)

And we probably will. After Trump, le déluge. I am completely convinced that the Sanders-Warren wing of the Democratic party that is at least condescendingly charitable towards the working class has zero chance of taking state power after Trump (or Pence, if Trump resigns or is impeached and convicted). Regardless of who is president, we will have a capitalist Republican Congress, and a majority of Republican state governments; the president will either be a Republican or an ineffectual Democrat. Just a few more Republican (or Blue Dog Democratic) state governments and the capitalist class can amend the Constitution; they will be sure to do so. (See e.g. Hungary.)

We will have a wave of nationalistic patriotism supporting some big war, perhaps against the Middle East, perhaps against Russia. We will have food rationing, gas rationing, medical rationing, and the working class will tolerate it. At least for a while. No one can predict what will happen then: we could all die, a socialist utopia might emerge, or anything in between.

Saturday, July 29, 2017

Actual examples of "censorship"

tl;dr: I do not at all support the freedom for anyone in academia to say racist stuff. Academia is a complicated environment with a variety of specialized functions; these circumstances make even a no-government-censorship comparison — much less a "free speech means I can say whatever I want wherever and whenever I want" comparison — completely inapt. Fredrik deBoer's article, Yes, Campus Activists Have Attempted to Censor Completely Mainstream Views, basically argues for a free speech right to be a racist asshole on a college campus, harassing, excluding, and marginalizing students of students of color, so long as that harassment is entirely verbal (or a "speech act", like painting a swastika out of feces). I can't think of a more egregious example of a leftist being a bourgeois stooge.

* * *

I'm about to begin my eighth year in academia. We in academia like to think of ourselves as objective seekers after the truth, unafraid to address even the most morally challenging issues and ideas, but even for the most honest and careful, it's never that simple. All research projects, even the physical sciences, are bound up in a lot of social constructions: what to investigate, who gets to investigate it, how it's investigated, and, crucially, how investigation affects the participants' status. In addition to being an institution (meta-institution) that engages in the objective search for truth, academia as an institution confers status, making it possible (or much more likely) for students and professors to achieve social positions of relative power, importance, and wealth. Finally, the university is not ideologically neutral: the university exercises substantial influence on the social legitimation and delegitimation of ideas.

Even a single university is also one of the most complicated coherent institution I've seen. Multinational corporations are larger, but they use a rigid authoritarian hierarchy to manage that size. Universities by their nature cannot employ this strategy. Universities do, of course, employ authority and hierarchy, but nowhere near to the degree of large corporations: a university cannot just tell a professor or student, "Do this task this way or you're fired." A university brings together scores or hundreds of faculty and hundreds or thousands of students, all of whom are pursuing interests of the utmost seriousness and making substantial commitments of time, and for the students, a lot of money. I lived in a commune of only about 30 people, and just reproducing the institution on a daily basis was an exhausting chore; trying to manage the interests, goals, preferences, and desires of thousands of people trying to do something they consider extremely important presents enormous challenges.

The notion of "free speech" and "censorship" is itself complicated. Just the most fundamental sense of the whether government may impose criminal or civil penalties for speech has generated entire specialties of legal scholarship and jurisprudence. What qualifies as "speech"? Under what circumstances can the government engage in censorship? What specifically justifies categorizing this as speech and that as action, and what justifies this censorship and not that? Just to address one narrow component of these questions requires a PhD thesis or a hundred-page Supreme Court decision. Trying to decide what constitutes "free speech" and "censorship" when we're considering the actions of people outside the government is a thousand times more complicated. When does criticism become censorship? When does expressing an opinion become harassment or oppression? How do we explore these questions when people are stuck with each other, when their relationship is fundamentally non-transactional? We cannot simply declare "free speech!" and automatically gain the moral high ground.

We also live under a system with profound privilege and power for Christian, white, male, heterosexual, and cis-gendered people. Members of other religion (or no religion), people of color, especially the descendants of black chattel slavery, women, queer people and people who do not conform to conventional gender norms have for centuries been marginalized, exploited, oppressed, assaulted, and murdered, often in genocidal quantities. The only "objective" questions are whether there is such social privilege, and whether those with social privilege have marginalized, etc. those without it. These objective questions has been answered decisively in the affirmative; to deny these manifest truths is akin to arguing a flat earth. Either you believe this oppression is good, and should be perpetuated, or it is bad, and should be eliminated, root and branch. There is no middle moral position, only arguments over tactics.

If a college professor teaches the flat earth in geology class, if they teach Intelligent Design in biology class, if they teach that vaccines cause autism in medical school, that professor should be fired. For their ideas. If that's "censorship", I'm OK with that.

When we were living together, my (now ex) girlfriend came home absolutely livid. She is black, and her (white, duh) professor told her straight to her face that black people can't learn math. She complained to the head of the department, and he was later gone. Is that censorship? Even if it is, I will say straight out, I'm perfectly OK with that sort of censorship. It was not only wrong, it was oppressive and harmful.

Recently, one of the math professors used an egregiously sexist metaphor in his class. The professor was forced to apologize; I believe the apology was actually sincere, but that's not the point: sincere or not, he had to make it, he had to make it good, or he would have been out on his ass. Again, I will say I'm fine that he was forced to apologize.

I am not, however, saying that anyone in the university — administration, faculty, or students — should have or seek the power to arbitrarily censor anything they don't like. I tutor freshman composition, and I have helped students write papers denying global warming, opposing vaccination, endorsing the hijab, arguing for creationism, and any number of ideas I disagree with. I don't want to tell them their ideas are wrong (my job is to get them to learn how to argue, and (sadly) how to craft grammatical sentences and coherent paragraphs), but even if I didn't think so, I am (as, I think, are their professors) obligated not to tell them that they're wrong and not to write about something else. One important component is that freshman have very little power, and a freshman comp paper will typically not be read by anyone other than the professor, so its potential harm is extremely low.

My point is that we have to think carefully about speech on campus, and not just shout, "Free Speech!" We have to look carefully at the effects of speech, and how this or that speech fits with the institutional constraints and goals of academia.

I do have a few principles more fundamental than free speech (in the sense that people should be able to say whatever they want without any kind of coercive social sanction). First, racism — by which I mean anything that is both false, stupid, or normative and that endorses, perpetuates, legitimizes, or erases the documented, proven oppression of people of color by white Europeans — has no place in academia. Period. People in academia should not say anything even a little bit racist. The government should not fine or imprison anyone or subject them to civil penalty for saying even egregiously racist things, but racists' protection ends there. No academic should ever express any racist idea.

And not just on campus. Both professors and students are public intellectuals, which confers special importance on what they say in public. If a freshman student even tweets a racist joke from home, they have no place in academia: they need to apologize and correct their behavior or go someplace that is not in the business of credentialing intellectual competence. If that is censorship, I'm openly, directly, and completely in favor. And if you're against that sort of censorship, well, I have to ask: what do we gain by legitimizing and normalizing — especially in an institution that proclaims its role at certifying intellectual competence — any sort of speech that perpetuates oppression?

So too with (just off the top of my head) sexism, hetero-normativity, cis-gender-normativity, and religious discrimination. As public intellectuals, academics have zero business perpetuating these evils. I don't care what you really believe; I just want you to shut up about them or get the fuck out of my university.

Sorry for the long-winded introduction to what will be an even longer post. I just want to make my position crystal clear.

* * *

On the one hand, bless you, Fredrik deBoer: in his essay, Yes, Campus Activists Have Attempted to Censor Completely Mainstream Views, he provides actual examples with links of the kind of behavior he considers objectionable censorship. For context, deBoer is a self-identified leftist, with a PhD in (IIRC) English composition instruction. (He's also a pretty good statistician.) On the other hand, I don't think his argument or examples are very good.

Just his claim is highly problematic in itself:

I absolutely despise the "impression" claim. This is pure concern trolling. Are these incidents actually creating anti-conservative bias, or are they just creating some "impression". Look, people have gotten the "impression" that I endorse the starvation of millions of people (I have been called both a Stalinist and a Maoist with precisely this implication) because I support a communist state, and not some infantile anarchist utopia. I am just not responsible for people's impressions that are not supported by the actual content of what I say. If you want to argue the fact, argue the fact, not impressions (which are probably self-serving and stupid) about the fact.

deBoer also makes a causal fallacy (For an excellent introduction to causal fallacies, see Siggy's excellent post, Trump’s Past Light Cone.) I agree that Republicans are fighting academia, and it is probably true that there is some impression of anti-conservative bias in academia, but the causal connection is unproven. As a competent statistician, deBoer should at least try to exclude reverse causality: perhaps the incidents that create the "impressions" are the result of, not the cause of, Republican opposition. There could also be other, unmeasured, causes influencing the connection (what we econometricians and statisticians call omitted variable bias). One hypothesis is that the professional-managerial class took state power from the capitalist class, but made a fatal mistake: they did not destroy the capitalist class as a class. The capitalist class regained state power, and they do not intend to make the same mistake: they want to annihilate the professional-managerial class and plow salt in their fields. The university, as the foundation of professional-managerial class legitimacy, is their most important target. Just deBoer's claim is a variant on the argument that leftist intransigence somehow created the racist alt-right, an argument that JMP demolishes in The Alt-Right Was Not A Response To Some "Alt-Left".

deBoer also conflates partisanship with ideology. (If he simply claims that Republicans conflate party and ideology, well duh. Of course they would.) As an employee of a public university and a public community college, I am required to be nonpartisan only in the sense that I am not allowed to endorse or condemn specific candidates, political parties, or ballot measures during an election. That doesn't mean that I have to be ideologically neutral (whatever that means). I can be for good ideas and against bad ideas. Indeed, academia as a whole cannot be even as ideologically neutral as the math department (and math has its own ideological norms). Academia is in the business of conferring or denying ideological legitimacy.

Even granting the most charitable possible interpretation of his argument, i.e. the noted incidents really do create "anti-conservative bias" (and not just some "impression"), and this impression really is the most important or dominant cause of the "collapse of Republican support" for academia, it does not then follow that we should refrain from these incidents. Much depends on what deBoer means by conservatism. If conservatism really does mean just the perpetuation of the white Christian patriarchy, with rigid sex and gender essentialism and norms, then academia shouldn't just have a bias against conservatism, we should be fighting conservatism tooth and nail, and not whinging when the racists, etc. fight back. It doesn't matter how much power theconservatives racists Republicans have: we won't undermine that power by not putting teeth in our demands.

On to the examples. (Links are original.) There are a lot, so this will take a while.

Student activists at Amherst University demanded that students who had criticized their protests be formally punished by the university and forced to attend sensitivity training.

This is not an original source; neither deBoer nor Katie Zavadski, the author of the linked Daily Beast article, link to the students' demands. However, the article does quote one demand, "that President Biddy Martin issue a statement saying that Amherst does 'not tolerate the actions of student(s) who posted the "All Lives Matter" posters, and the "Free Speech" posters.'” "All Lives Matter" is facially racist; according to Zavadski, the "Free Speech" posters are related to Robby Soave's article, Students: Fight Racism, Not Free Speech, which seems to defend the rights of "a random jerk in a truck shouting racial slurs at Mizzou’s black student body president and [those who created] a swastika made of feces appearing on the wall of a residence building." Color me censorious, but I'm 100 percent with the Amherst students.

At Oberlin, students made a formal demand that specific professors and administrators be fired because the students did not like their politics.

The formal demand appears in a 14 page manifesto, alleging pervasive and egregious racism at Oberlin. Presumably, deBoer refers to this specific demand on p. 12, reproduced in full (I cannot copy and paste; I apologize for any errors in transcription):

So basically, the students are demanding that administrators be fired for racist incompetence, and professors for just being racists. Although their punctuation is atrocious, I'm with the Oberlin students.

"The Evergreen State College imbroglio involved students attempting to have a professor fired for criticizing one of their political actions."

This is a little more gray. But the students who are demanding Professor Weinstein be fired not because he criticized their political action (asking white students instead of minority students to observe the Day of Absence) but because they saw his criticism as specifically racist in character. I'll take the professor's side on this one, at least tepidly: I don't think professors should have the freedom to say racist things, but I don't think he said anything actually racist; if he had, he should be fired.

At Wesleyan, campus activists attempted to have the campus newspaper defunded for running a mainstream conservative editorial.

Neither the article nor deBoer link to the offending Argus article; I assume they mean Bryan Stascavage's September 14, 2015 article, Why Black Lives Matter Isn’t What You Think, which seems pretty fucking racist.

Regardless, there is not now nor has there ever been a free speech right to funding anywhere. This issue is about whether the student government has a right to control its own money.

A Dean at Claremont McKenna resigned following student backlash to an email she sent in response to complaints about the treatment of students of color.

God damn, but saying that minority student's "don't fit the C.M.C. [Claremont McKenna College] mold" seems just a wee bit racist for the president of the college.

The trend seems clear. Maybe I'll get to the rest later, but I suspect they'll all be the same.

I do not believe that anyone — student, staff, faculty, administration — has a "free speech" right to be a racist, sexist, etc. on campus. If you're fighting for this right, you're fighting to let racist, sexist, etc. conservatives violate the rights — including the free speech rights — of people of color, women, etc. The question is not whether we support this or that rights, but whose rights we support: the bigots' or the victims.

I'm about to begin my eighth year in academia. We in academia like to think of ourselves as objective seekers after the truth, unafraid to address even the most morally challenging issues and ideas, but even for the most honest and careful, it's never that simple. All research projects, even the physical sciences, are bound up in a lot of social constructions: what to investigate, who gets to investigate it, how it's investigated, and, crucially, how investigation affects the participants' status. In addition to being an institution (meta-institution) that engages in the objective search for truth, academia as an institution confers status, making it possible (or much more likely) for students and professors to achieve social positions of relative power, importance, and wealth. Finally, the university is not ideologically neutral: the university exercises substantial influence on the social legitimation and delegitimation of ideas.